Spring 2020 Connections Alumni Profile

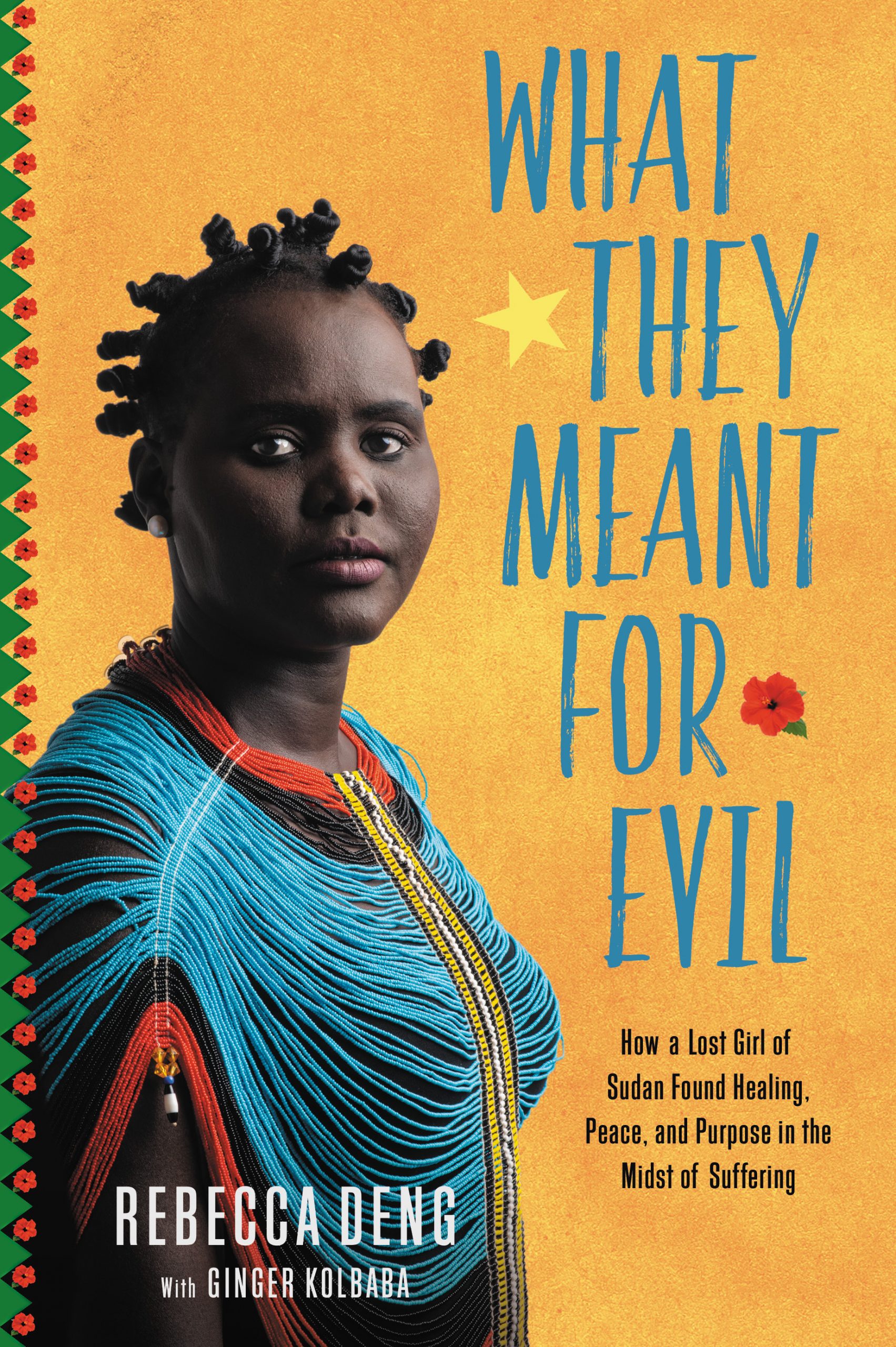

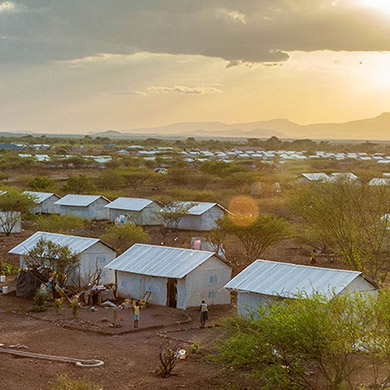

Last fall, Rebecca Deng ’04, who happens to be a remarkable story teller, published her biography, What They Meant for Evil: How a Lost Girl of Sudan Found Healing, Peace, and Purpose in the Midst of Suffering. In her book describing how she was orphaned through the Sudanese War, and lived most of her childhood in the Kakuma Refugee Camp, Rebecca focuses on how it is possible to endure all she did, and afterwards to live a life of healing and meaning, thanks to so many who helped her out in so many ways. But most of all thanks to the graciousness of a God that she was irresistibly and mysteriously drawn to, even from a young age. And in the middle of a refugee camp.

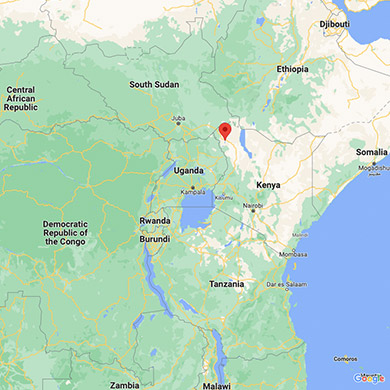

Rebecca moved to Holland, Michigan when she was 15 and straight out of the Kakuma Refugee Camp in northern Kenya. She had lived there for the previous eight years, after fleeing southern Sudan at age six with her uncles and aunts and cousins in the Bor Massacre of 1991.

You can read that whole fascinating story in her book.

One of only a handful of female Sudanese orphans brought to the United States in the year 2000, when it was “the Lost Boys” who were getting the media attention, Rebecca was taken in as a foster child here in Holland by Rachel and Lennis Baggech. The then-recently married Baggeches had just returned from Kenya themselves, moving to Holland for work. Always interested in humanitarian aid and missions, they wandered into Bethany Christian Services (BCS), and were asked by BCS if they would take in foster kids from the Sudanese refugee camp. They first said yes, found out they were pregnant with their first child, were told by scores of people it would be crazy to take in foster teens with a first baby, backed out, but when it felt so wrong, stepped back in, taking two teenage girls.

“It was a hard yet beautiful time of adjustment. Some days we’d laugh so hard we cried, and some days we just cried, but I wouldn’t trade anything for it,” Rachel Baggech still says. “You make one decision and it unravels a whole different path for you. But I’m a Christ follower and not a culture follower—the thing that binds all of us is Christ, finding the commonality of our faith.”

Not that things were easy by any means. Rebecca didn’t have the words or the emotional wherewithal at that time to share her feelings. She came in November, of all months, to Holland, Michigan from a hot sunny desert, and had never before seen snow. And had lived a life of trauma for basically the past 10 years.

But she also “didn’t have to worry about people breaking and entering. I had breakfast, lunch and dinner! I could feed my physical body, and dreams ahead!” Rebecca said, remembering fondly the breakfast of Kenyan-style porridge Lennis Baggech made for her that first morning.

HCHS was basically Rebecca’s first real schooling, she said. And both she and her foster sister Teresa were HCHS’s first real English Language Learners (ELL) students at that time. “They didn’t know what to do with me,” she admitted. “At HC I was in formal school for the first time in my life, and I had the English of a second grader!”

”Suffering is not sexy, but there is no amount of brokenness that can't be overcome...there is room for healing and transformation—though for it to take place, you need a village around you!

But it worked, eventually, though not always perfectly. But it worked well enough for Rebecca to write a book almost 20 years and two higher degrees later.

“Being at HC was what I needed when I came—it was the best place for me,” Rebecca said. “It was a high school where I had my own space to learn about who I am as a person—as an ESL student, as a person of color in [a white] environment. The one thing that was really helpful was the kindness that I needed and that stood out—from both teachers and students.”

Choir with Mr. Bird was a favorite class, an easy way to learn English: “There’s something about singing—if I see a word and sing it, it just flows. Singing is good for learning a new language!” she said. “Plus, it’s an orchestra of different voices—you’re free to express yourself, but you are working together! We can be a choir and celebrate different tones!”

She loved other classes too, especially Bible with RVL. But it was a story, a book about another African refugee who eventually graduated from Harvard, (Of Beetles and Angels: A Boy’s Remarkable Journey from a Refugee Camp to Harvard by Mawi Asgedom) that her HCHS English teachers, Kathy VanTol and Deb Bandstra, shared with her, that was a turning point. It helped launch Rebecca Deng out of how she saw herself at the time into future possibilities.

Because she realized even then, that if she just looked at herself on the outside, she didn’t necessarily look like what people would judge as successful: “You are a girl, a black girl in a school [of mainly white students], a teenage mother, an ESL student…therefore you are not going to do well. Those are the voices that diminish hope in people,” Rebecca said.

But “once I made it through [the book], I thought, that’s me! I can do that—finish college, maybe I can do grad school. That’s the empowerment of different voices and diversity in literature, because everyone wants to see themselves in stories, in successful stories,” she added.

Because things got really complicated the summer after her first year at HCHS, when she and the Baggeches realized that Rebecca was pregnant, from being raped the day before flying to America. Complicated, more difficult, but certainly not impossible.

With the help of the Baggeches—who had gone suddenly from double income no kids to two teenage girls and two babies in diapers—along with her HC support system of teachers and circle of friends, Rebecca graduated from Holland Christian four years later. And then graduated from Calvin College another four years later.

It was when she was working for the American Bible Institute, married to her Calvin sweetheart (another great chapter of her book), and not sleeping the last month of her pregnancy with their now four-year-old son, while absorbing the news of hurting children at the US border that she started writing her memories down. She realized she was protected, had a house, safety, yet struggled with introducing her son to a world that wasn’t welcoming or friendly, where so many young children struggled.

So she started writing her book on her iPhone, in the middle of the night, when she couldn’t sleep.

”God only says you are beautiful, you are a treasure, you can do this. I am a God of abundance, I can provide.

“There was something that jerked the memories, made me think about childhood things I had put away, and those memories came out,” she said.

The colors and the smells she remembered the most vividly, but anything she thought she remembered, but wasn’t sure about, she verified via phone with her uncles and aunts and cousins, now spread throughout Sudan and the world, their home villages obliterated in the war. “Is this true?” she would ask, “and they were like yes or no—especially the uncle’s wife that was running with me during the war.”

She realizes she was “one of those kids that pay attention to a lot of things, and think about them more.” Rebecca recalls one instance back in the refugee camp when other refugee kids bullied her, saying since she was the only one left in her family, she must have hurt them.

She cried the whole day, wondering if she really had hurt her family.

But then she distinctly remembers praying to God, something she had learned from the group of Christian women in Kakuma who had taken her in, mothered her, and taught her about life, her body, worship, and the Living God, “God, please, give me Your truth and only Your truth, so I can tell the difference.” And she then remembers feeling His peace, realizing how wrong those kids were.

Part of Rebecca was reluctant to share her story even this many years later, with so much trauma to relive in the process. But her hope throughout the writing and publishing was that “If I share it, it might help somebody that is going through a dark time, that actually you can do it. Suffering is not sexy, but there is no amount of brokenness that can’t be overcome,” she continued. “If [a traumatic event] didn’t kill physically, then there is room for healing and transformation—though for it to take place, you need a village around you!”

Since her book’s publication, Rebecca, her husband and children have stayed settled in Holland for the time being, as she promotes the book and fills speaking engagements.

And when those belittling, mocking voices periodically return, reminding her of her childhood trauma, of what she may look like on the outside to others, she has learned to hear her heavenly Father’s voice instead: “No this is not from God—he only says you are beautiful, you are a treasure, you can do this. I am a God of abundance, I can provide.”